Project

2

- Constructed Views Liverpool Painting: A Social Landscape

Rochdale

Art Gallery 25th February -24th March 1984 Pete Clarke's

activity as an artist has interested us for a long time.

He is a 'founder member' of the Liverpool artists' workshop,

evidence of a new and exciting move by artists to determine

their own structures and to effect grass root links with

the public. As a committed member of the Labour Party, he

is actively engaging in the the political struggles of Liverpool

and is trying to find new ways in which art can effectively

operate within the political struggle. We feel then that

his work offers new meanings and resolutions for the role

of artists in society.

Artists and the practice of art making are marginalised

in our society; art is no longer a concern of most people.

Pete Clarke is an example of an artist who cares about bringing

art back to the people and who recognises the potential

of art as a powerful social force. From the Gallery's point

of view, as a public institution, we are finding new ways

of establishing a direct and meaningful relationship between

the living artist and the public-to establish a participatory

culture. In promoting the work of Pete Clarke, an artist

who deals with issues that are direct in determining the

quality of peoples' lives, we hope to lay the foundations

for a positive interaction between the public and the artist's

work.

Art

is severely under threat in the 1980's. To counter the concept

of art as a peripheral and elitist activity, we hope this

exhibition will go some way to realizing the true potential

of art, as a positive force in society. We are especially

indebted to Peter Clarke who has involved himself in all

aspects of organisation of this exhibition and for his commitment

to the Gallery and its policies. Also, thanks are due to

North West Arts for their financial support and to David

Campbell for his contribution to the catalogue and to the

argument of the show.

Bev

Bytheway/Jill Morgan

Rochdale Art Gallery 1984.

____________________________________________________________________________________

I

was born in Burnley, Lancashire in 1951 but lived most of

my school life in Nelson, a small cotton-industry town in

the Pennines. After leaving secondary school I went to the

local Foundation art course at Burnley Municipal College.

This "Traditional" drawing based course has been

an important influence on subsequent work. Afterwards I

was a student at Bristol Poly and Chelsea College of Art.

In 1978 I was lucky to get a job in Liverpool, a city full

of contradictions. The history of this once thriving port

and mercantile centre reflects strongly on daily experience

and has been a major influence on the subject of my work.

The city is bearing the brunt of the recession, ravaged

by unemployment, redundancy and poor housing conditions:

and can be seen as a symbol of political decline. It is

important that the work has social and political relevance

and attempts to describe the experience common to many people

living in an industrial centre, by asking simple questions

which demand political solutions.

The

making of art can be used to sort out ideas and thereby

help understand social problems. At Liverpool Artists' Workshop,

a communal studio with 14 members, we try to evolve different

ways of using art by making it more accessible. We open

the workshop, have discussion and lecture programmes and

attempt in other ways to reach differing audiences in the

community. Recently, as an example of this, I worked with

St. Helen's Play Council designing and painting a play bus

about the mining history of the town with youth and unemployed

groups. We feel that these many functions of art have potential

and that as a group we can make a useful contribution.

Pete Clarke

January, 1984

____________________________________________________________________________________

Arriving

in 1978 to take up a post in the Silkscreen department of

Liverpool Polytechnic, Pete Clarke came to a city ravaged

by long term unemployment. Since then, the economic strategy

of the Conservative government has effectively amounted

to a de-industrialisation of Merseyside, which has produced

a state of accelerated dereliction that is all too visible.

Just one example of this economic devastation can be indicated

through the collapse of Liverpool's traditionally based

industries of sugar importation and refining, sugar cane

has been replaced by beet as the raw material for sugar

production. Liverpool's cane based sugar industries have

thus been made redundant, creating a chain of unemployment

which is still in operation.

As an active member of the Labour party in an inner-city

constituency, Pete Clarke responds to this situation politically

through the workings of his local Labour party and in terms

of an art practice. This exhibition serves to indicate the

manner in which these two activities, amongst others, interconnect

and it will provide a useful contribution to an analysis

of the sort of problems this activity presents.

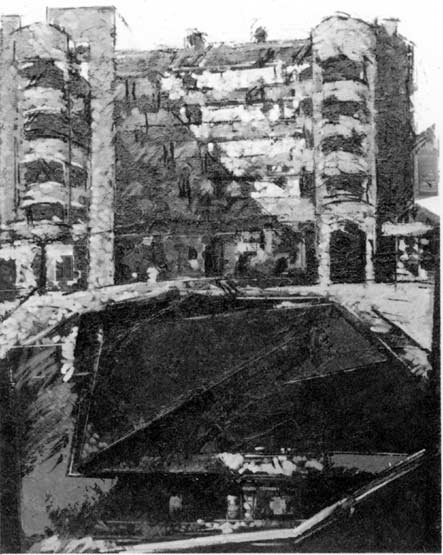

Having worked mainly in the area of silkscreen printing

and drawing, the painting 'Liverpool 8' represents Clarke's

first serious return to painting. A possible point of interest

of the work may lie in Clarke's attempted production of

a politicised art and as such may indicate the kind of questions

Clarke perceives thus to involve and the procedures he set

about employing to secure public understanding.

In terms of this intervention it is perhaps not so surprising

that Clarke would draw upon those means of representation

in which he had some familiarity. Having been trained in

a fairly "traditional" realist approach, it was

this practice which was brought to bear in 'Liverpool 8'.

Its applicability may rest for Clarke in the way it attempts

to construct looking, taking its historical cue from Cezanne,

as a fluctuating dialectical process in which the sense

of interconnection is articulated at the level of formal

construction.

As is always the case, simultaneous with the question of

how to paint is that of what to paint and for Clarke this

problem was of attempting to produce work in which questions

of political engagement are raised. The device he adopts

is the use of metaphor. 'Liverpool 8' consists of a realist

representation of the back window of Clarke's flat, and

as such would be able to be accommodated within a fairly

established genre of representation. There is no overt recognition

of political significance, not until that is the painting

is contextualised by the title. Before July 1981, 'Liverpool

8' had very little meaning for most of the country, although

within Liverpool it did have particular connotations beyond

that of a mere postal district. After the riots of July

'81 this situation was altered: 'Liverpool 8' was given

meanings repeatedly and hysterically; it seemed at times

during that summer that the need for 'Liverpool 8' to have

meaning had reached almost obsessional proportions in the

mass media. Often based on political positions, 'Liverpool

8' was constructed to mean anything from the confirmation

of racist assertions of open conflict, to the long awaited

collapse of Capitalism as predicted by certain groups on

the left. Yet whatever meanings were produced and employed,

one thing is certain and that is that 'Liverpool 8' is a

sensitised term which sparks off a chain of political readings.

The construction of meanings operating beyond the limited

control of the painting, produce definite procedures for

seeing the work. The bars on the window occupy an important

position around which readings of the painting can be made.

Clarke appears conscious of this process and utilises it

through the degree to which the barred window can be read

metaphorically in terms of containment, exclusion, keeping

people/things in or out. That which has been termed the

political concern, is thus brought into issue through the

metaphor and the title. What Clarke is attempting to pose

is the question of political engagement; does one become

involved in the political world 'out there' beyond the bars

or does one retreat behind them so that the world remains

literally, a view, out of the window.

The paintings 'Liverpool 8' and the 'New Socialist' are

interesting because they indicate the conditions which are

necessary for metaphoric reference to work, namely the degree

to which the metaphor has public accessibility. In the 'New

Socialist' again the question of engagement/apathy is a

motivating factor in the production of the painting. Intended

specifically to be raised through the metaphor of the chair

as activity/passivity, the work indicates how particular

meanings intended by the artist may escape public reading

due to obscurity of the metaphoric reference. Asked about

the function of art, Henri Matisse replied on the lines

that a work of art should be like a comfortable armchair

in which a tired business man could relax. The painting

uses the concept of the chair as a metaphor for art's function,

and Clarke, by his usage, signals a challenge to that definition.

His is not the comfortable chair of Matisse, to indulge

passivity, but rather it implies a more functional, almost

educational role.

This

whole speculation is based on the understanding of the metaphoric

role of the chair to Matisse and the function of art, an

understanding which demands the viewer to be familiar with

a very specialised knowledge, twentieth century art history.

It is because of this that the Matisse facet of the metaphor

is largely unreadable, whilst the more general metaphoric

value of the chair as a pointer to the question of activity,

is open to a public reading. The political aspect of the

question of activity is posed by the contextualisation offered

by the collaged elements incorporated in the work.

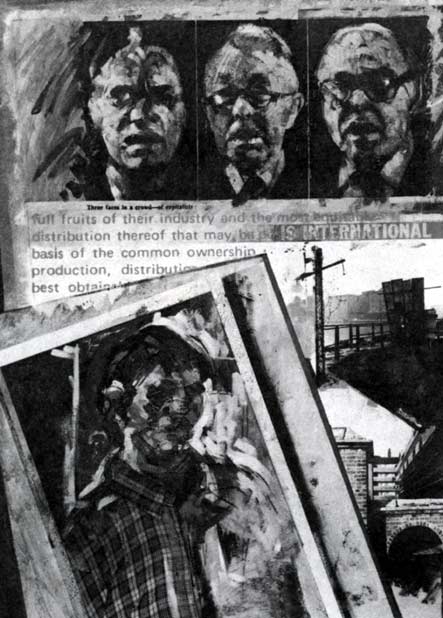

The

value of collage is greatly employed in the Triptych painting,

functioning as a commentary to the painted areas. Again

the use of metaphor is taken up in these works by adopting

a restricted dark tonal paint range to represent dereliction

in the form of housing estates and factories. Clarke deliberately

attempts to make use of the established public tendency

of associating particular colour ranges with psychological

states. The derelict architecture is thus painted in a dark

tonal range, attempting to promote a reading which draws

off these colour associations in terms of depression and

gloom and which by extension are hoped to represent the

social condition of despair.

The painted areas are further invested with metaphoric value.

Although the representations are of buildings within Clarke's

local constituency of Riverside, they are intended to work

as metaphors for the disintegration of Capitalism as an

economic system. This may be an error of method, for although

dereliction is a position within the functioning of the

Capitalist system, it is perhaps only an extreme form. By

taking this extreme form as the metaphor for the complete

system, the degree of public recognition of the analysis

may be limited. Capitalism after all is able to produce

pleasures and due to the effectiveness of its ideological

apparatus is still able to convince the public that it is

the 'only way' and thus secures the conditions for the reproduction

of its relations of production. Perhaps it is the level

of generality that the metaphor invokes which is the problem.

People do not experience 'Capitalism' in a brute form, in

fact they are largely unaware of its action in terms of

an organised economic category. Rather it is their relations

within a number of specific practices, housing policy, education

and health amongst others, in which they are regulated by

capitalism. Representations of dereliction in Liverpool

can no more claim the status of typifying capitalism than

can representations of micro chip firms in Milton Keynes.

The

selecting out of these points of contact is attempted by

Clarke, still operating within the colour/psychological

state equation. Arranged as the counter term in the colour

metaphor, he selects representations which possess colour

literally, thus playing off the associations that are brought

in relation to the dark gloomy areas. Against the stark,

monumentally constructed areas of architectural landscapes

which produce spatially, and, by implication, socially oppressive

environments, he sites points of resistance. The sites he

constructs as points of hope within the landscape of decay

are those activities which offer some form of potential

future. Labour party buildings, socialist organisations,

Co-op halls, political posters, ironic and humorous graffitti

are all collaged in the work in the form of colour photographs.

Opposed to the oppressive generality of the painted and

black and white photographed areas, the colour photos of

Clarke's perceived points of resistance are intimate in

scale. But beyond this, the sense of intimacy is enhanced

by the actual means of representation used. The small colour

photos have associations of personal use, snapshots as a

source of pleasure. Certainly they do not have the aspect

of official documentation which the stark black and white

photographs seem to possess.

The

selection of the points of resistance are of course determined

by Clarke's political consciousness, and as such are constrained

by particular ideological boundaries. He does not attempt

to claim that it is an unmediated duplication of reality

but sets about the organisation of the paintings in terms

by which particular relationships are set up between the

various elements. This procedure of implying relationships

is also articulated through the painted areas which adopt

a cubist derived technique of multiple viewpoints to produce

jarred spatial planes, emphasising interconnection.

In

the more recent works the selection of elements are less

rigorously limited to overtly socialist themes. Instead,

some of the complexity of capitalist ideology is articulated

through the use of irony to set about the construction of

meaning. For instance, what does it mean to take up representations

of Queen Victoria in 1984? It is not merely a matter of

aesthetics, for the Capitalist's themselves show us that

the contestation of this kind of representation is important

at the level of ideological and political struggles. It

actually matters how things are represented, it is important

to contest the practices in which representations are constructed

and by which meanings are fixed. This concern with representation

brings in questions of who it is that actually gets represented,

by what means, and for whom. It does not simply involve

representation in terms of statues of the ruling class,

although the question of whose history is being recorded

is posed by analysis of these forms. The activity of intervention

should be carried out across the whole of the social formation

in which representations are produced, from the media coverage

of an industrial dispute to the meanings constructed for

Victorian values by a Conservative Prime Minister in the

throes of dismantling the Welfare State.

It

is the problem for Clarke and all others involved in practices

of representation, to what extent can they intervene in

the codes and procedures widely in use for the production

of meaning? This does not mean the simple adoption of these

procedures, for this would merely duplicate the dominant

ideology, rather it consists in contesting the means by

which meanings and truths are organised.

The work in this exhibition indicates the possible procedures

of achieving this, adopted by one particular artist, and

as such demonstrates the problems that are posed, but also

the rewards that this attempt may bring.

David Campbell January, 1984.