Project

12 : Collaboration Pete Clarke and Georg Gartz

Conversations

in Colours

Sometimes a painter discovers in the pictures of another

artist a surprising proxi¬mity to his own work. Maybe

it is the colours, maybe the way in which the brush is

used. Maybe it is the mysterious harmony of the many small

parts that make up the whole. Or even all of these things

together. At the same time this feeling of proximity is

combined with the awareness of dissonance within the similarities;

this ounce of uniqueness which distinguishes the handwriting

of one painter from the next and makes it unmistakably

individual.

Fifties

Cathedral

(Acrylic on canvas,100 x 100 cm, Oct. 1999)

But

what happens when two such related painterly styles come

together: on one canvas, in one picture? This does not happen

often, for after all art is generally an individualist enterprise

and artists independently minded as most of them are avoid

collaboration in joint pictorial projects. Possibly this

is because they feel worried that they themselves would

disappear in the process and cease to be the person who

they are only through their art. Possibly, however, the

main reason is that they have not learned that artistic

collaboration involves more than conversa¬tion with

oneself but rather also a dialogue with another person.

Since the Enlightenment art has been presented time and

again as a lonely, often tragic adventure, full of freedom

and individualism, without compromise, often hermetic and

incomprehensible. This idea defines the myth of art to the

present day. Most artists seemingly put far more emphasis

on their individuality than on the subject and content of

their work. Increasingly the individuality of artistic handwriting

became the core issue of art and since then every artistic

statement that could cause this individuality to diminish,

has been avoided as a place of great danger.

But why should the brush strokes of two artists not touch

each other like the fingers of a hand? And does it not suggest

itself that painters too, should occasio¬nally work

jointly like lone athletes who occasionally invest their

individual skills in a team effort and thus let their individual

strengths and weaknesses appear in a wholly different light.

(Many artists are even opposed to such metaphors.) For this

one needs two quiet reserved characters who are prepared

to let another person make use of their own colours and

forms. They have to be open and relaxed souls, full of trust

that in the exchange with the other their own work can be

altered but not destroyed. And they have to possess the

curiosity that makes them want to see their own colours

and artistic gestures in an unexpected manifestation. All

this is true for Georg Gartz and Pete Clarke who met each

other three years ago.

Yellow

Cathedral

(Acrylic on canvas,100 x 100 cm, Oct. 1999)

Before Pete Clarke showed some of his pictures in an exhibition

in the Lichthof in Cologne, Georg Gartz had already seen

them in his Liverpool studio. And for his part Pete Clarke

got to know the paintings of the Cologne artist Georg Gartz

in his studio before he showed his works in the Basement

Gallery in Liverpool. The exhi¬bitions were part of

a lively exchange between artists from Cologne and Liverpool

which has been going on for some time between the two cities.

One reason for this exchange is that despite the idea of

European union people in the Northwest of England and those

in the West German Rhineland actually still know (too) little

of each other. Is modern art, which after all has been recognised

as an international language, the same in both regions?

Have individual experiences of painting the same foundation

in both areas? And does the love of colour possibly transcend

all influences of society by touching sentiments which are

the same all over Europe?

Georg Gartz and Pete Clarke told themselves that here was

an issue which was ripe for discussion in painting. Thus

they started to exchange their experiences on canvas.

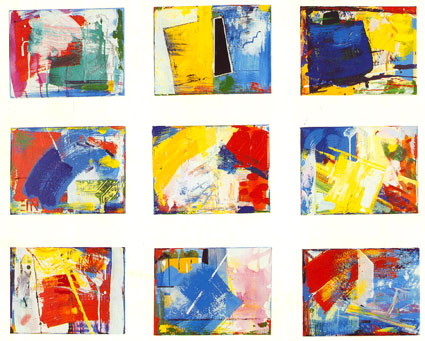

What is important is that the joint works of Pete Clarke

and Georg Gartz do not just represent the sum of two approaches

but that a new third conception has emerged which is more

than the sum of its parts. The painters leave enough room

for each other on the canvas to let a dialogue of colours,

shapes and pictorial gestures arise. One painter starts

it all; with a colour, with a undefined outline and the

other continues it. For the time being each one leaves untouched

what the other has painted. At first the transformation

happens by means of addition so that the picture becomes

increasingly dense; the change happens through a gradual

process of growth. They work very carefully in order to

avoid destroying and erasing the other's brush strokes,

even if this cannot be completely avoided. The canvas is

not understood as a battlefield but as a zone of deliberate

and careful understanding. Out of a trickle of colour arises

the outline of bridge. An alarming red is soothed by its

surroundings. A box like shape protrudes from the colour

like a persistent signpost and many fluid traces come together

to form a resting structure.

Magenta

and Yellow Facade

(Acrylic on canvas, 50 x 50 cm, March 2000)

Pete and Georg always work on more than one picture at the

same time. After they have swapped and continued their pictures

several times without comment they finally start a verbal

dialogue. The talking is part of the collaborative creative

pro¬cess. They talk about how they should proceed or

if they should add something here or cover something there.

Each has different ideas and experiences as to which colours

work as a harmonic whole. Especially the drawings (which

appear harder edged than the works on canvas because the

paper does not soak up the colour) show that the painting

is also a matter of opposing dynamics: a layering, and extinguishing

of colours and marks which the other has previously placed.

One painter gets into cul de sacs and dead ends with his

colours and the other will once more set in motion or simply

see something different. In any case crea¬ting harmony

is a difficult process.

Does one painter question the other? Does his addition extend

the possibilities available to the other? What does it mean

to question and to assert ones personal creative impulse

in the process of exchange? What does it mean to accommodate?

In this way the creative process becomes a model of a dialogue

of equals. Colours are placed into space, tentatively or

boldly, carefully or distinctly, slightly questio¬ningly

or as A confident statement and always begging further comment.

The objective is to react to a painted comment: to dovetail

or to contrast. One artist picks up the colours of the other

and adds his own colours. Colours approximate each other,

resist each other, confront each other as strangers and

challenge each other. They embrace each other and illuminate

each other, stick to another, rub against each other or

appease each other. They hover or mingle in dense crowds.

Layered

Like glass.

(Acrylic on canvas, 50 x 50 cm, March 2000)

They appear as whisks or as organic scatterings, as a trickle,

the impression of a material, a splash or a geometric shape.

Innumerable abstract fragments interlock to form an insoluble

unit and the balance of colours comes to represent the balan¬ce

of life as a whole. There are countless possibilities of

losing and re finding one¬self in the colours. Only

the creations of one painter make it possible for the other

to arrive at his own creations. The painted reactions alternately

become barriers and complements, forces of resistance and

brackets. Thus it all adds up.

Indeed, most of the pictures by Georg Gartz and Pete Clarke

have a motif that in many cases has been rendered unrecognisable.

In some paintings an architectural shape sticks out such

as the outline of a church, a tower, a high rise block.

The other canvases appear abstract images of turmoil that

have found their balance in a state of anonymous dynamism,

in the tension of opposites, as a harmony of differences.

The results are pictures of manifold permeation in which

the contribu¬tion of each painter has been blurred.

Often the artists themselves have difficulty retracing their

steps. This experience is as much part of artistic contact

as of every other type of communication.

SmallKoln

Paintingl.

(Acrylic on canvas, 30 x 40 cm, Oct 1999)

Georg

Gartz and Pete Clarke never paint simultaneously on one

canvas but they always take turns. They also work on more

than one canvas at the same time. One begins to talk, the

other replies, then again the first and so on. Each according

to his own abilities, his own ideas, each against the background

of his long standing experience as an artist. The paradox:

the process causes the characteristics of the painters individual

hand writing to change and to disappear in a larger whole.

Clarke, whose paintings are often characterised by figurative

elements, fragments of writing and architecture, even flower

motifs, plunges into Gartzs freely abstract colouring and

is led to greater abstraction in his own use of colour.

Gartz, on the other hand, who has long banned figurative

elements from his painting, is led by Clarke to the edge

of figurative depiction. The greatest artistic achievement

in every picture is its balance and that is achieved when

neither of the two artists wants to add any more touches

of colour. Indeed they manage to integrate their in¬dividual

artistic handwriting into one joint work and thus to subsume

it in the whole for a moment. This points to an exemplary

concept: to use individual experiences and possibilities

in such a way that a common experience is created and this

rela¬tivises the myth of (artistic) individuality to

a significant extent.

A new artistic category is introduced: artistic creation

functions as a bridge to active mutual understanding. Painting

as a coming together through colours. Probably it is no

coincidence that both artists also work as art educators:

Pete Clarke as Senior Lecturer in Painting at the University

of Central Lancashire and Georg Gartz as Museum Education

Officer at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne. It is characteristic

of both that they do not separate their educational artwork

from their painting but regards it as an experience that

their painting also benefits from.

Naturally, it did not all come together harmonically right

from the start. Artistic colla¬boration is a matter

of achieving a finely tuned balance. In the first joint

works it was sometimes still the case that one painter dominated

the picture, not on purpose but still unmistakably visible

(maybe because one painted a touch more boldly, maybe because

one was more careful). Ideal balance was only achieved after

the second or third painting session, especially because

both artists possess the rare gift of measured self restraint.

Their painting is marked by reciprocal empathy not by competition.

Both have reliable intuition when it comes to harmonising

colours even if they represent disjunctures and contrasts.

Both are seeking the orchestration of many smaller elements

in a coherent whole rather than allowing one expression

to dominate. And neither is interested in posting obvious

messages but in the quiet yet exciting subtlety of a process

of painting in which the opaqueness of our experience gives

rise to poetic feeling. Joint painting of this kind is an

open, intentionless dialogue. It is the art of being sensitive,

curious (that is, hungry to experience the new) and without

hidden agendas as attentive to ones own emotions as to those

of the other.

Of course, Georg Gartz and Pete Clarke are not the first

artists who have painted pictures together. In the 1980s

Andy Warhol and Jean Michel Basquiat worked on several large

scale canvases in which Basquiat's brattishness enlivened

Warhols tired art stencils in an unexpected way. Several

decades ago Dieter Roth and Stefan Wewerka created wildly

animated joint works out of the mood of their meetings.

The Fluxus artists in their most radical period in the middle

of the rebel¬lious sixties were also very keen on the

collaborative art project. And the so called Young Wild

Ones, painters of the 1980s such as Walter Dahn and un Dokoupil

occasionally collaborated in a painting in order to satiate

their hunger for pictures. And then there is the group of

painters who only ever appear in public as a couple but

that is yet another story.

The fact that Georg Gartz and Pete Clarke come from different

countries only makes their common artistic project even

more compelling. It is not the fashionable Crossover that

is introduced but the ideal of a synthesis in which the

question after the difference is no longer important. They

have found a way of collaborating that has long been employed

in the sessions of Jazz and Blues musicians. Against the

background of a common sound environment and on the basis

of a shared motif musicians of the most varied cultural

circles develop an individual style, improvising with great

enjoyment, in order to then integrate their individual conception

into the larger body of music. Both artists like Jazz. And

the fact that they listen to music while they paint confirms

that in their art they put more emphasis on the right rhythm

than on theoretical concepts.

Jurgen Kisters

Köln Hdhenhaus, March 2000

(Translation: Dr. Christina Thomson)

Acknowledgements

We first thougt it would be fun and interesting to collaborate

together on a painting project during 'Eight Days a Week'

in Cologne 1998. Since then we have been working together

like two jazz musicians in a creative dialogue revisiting

ideas about authorship, spontaneity and authenticity in

contemporary painting.

We are excited by the work we have made, but it would never

have happened without the encouragement and support of many

people, institutions and friends.

We would especially like to thank, Jurgen Kisters, Bryan

Biggs and 'Eight days a Week.