Project

7 : Connections: Liverpool and Manchester

Connections and Contradictions (The Burning of the Town

Halls), Text by David Campbell 1986

For some, Connections is clear; such an assertive title

for a body of work, pregnant with possibilities. It offers

itself up as a context from which a yield of forthright,

if not definitive statements could be obtained. Not only

does it seem to guarantee 'conclusions', but it also assumed

a straight- forward process of meaning; one which is diagramatic

-even illustrative.

Premised upon the belief that the author of the work will

somehow direct a transfer of' information' in the form of'

facts' derived from the 'real world' in a form which will

best illustrate the privileged vision of the author. All

that is required from the viewer is the reception of this

'meaning' communicated to her/him when this is completed

we can all bask in the obviousness of the insight, now apparent

to all, the conclusions-the connections have been pointed

out and we are without darkness!

Within the cluster of terms orbiting 'connections' and its

potential meanings, it would seem to me those of fact, truth,

evidence, proof and understanding are central to its working.

In the caricature form of visionary outlined in the first

paragraph, these points of reference are seen as unproblematic;

they fall into place in a mechanical procedure which commences

with 'facts', discovered by the artist, being communicated

through the work, culminating in 'truth' being offered to

the viewer to accept. It is simple, clear-cut, mechanical

as far as I'm concerned, a complete fantasy.

|

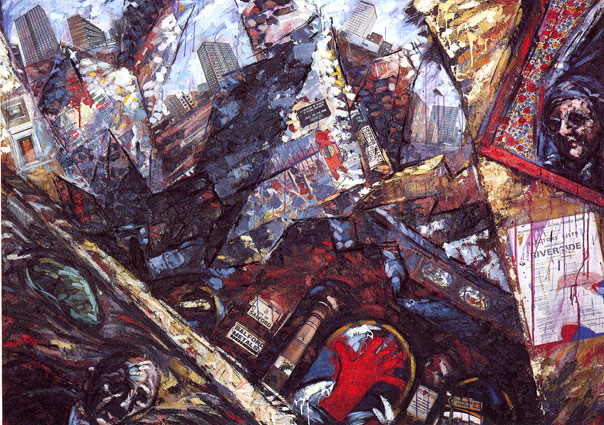

Municipal

Modernism: The Cloth Cap and the Red Glove |

Connections and Contradictions (The Burning of the Town

Halls)

To begin with it adopts the lumbering hypothesis of the

form/content distinction, here in the guise of a 'content'

about Manchester and Liverpool in political, economic, social

or cultural terms which exists, yet has to be given form

to be understood. The 'form' is the 'artistic bit', that

which will deliver the 'content'; into which the content

will be poured. Form must allow itself to be consumed by

content, and yet be as transparent as possible, it must

not interfere with the meaning of content. For those who

operate by this rationale, and there are many, the normal

state of affairs is to describe the 'form' as neutral, allowing

the content to be judged in respect to a hierarchy of values

set elsewhere. 'Good old form' is just form, untouched by

history or ideology; it can be resalvaged and brought back

within the citadels of aesthetic purification, after convalescence

and cleansing it can be protected from those unsavoury kidnappers

who, in their philistine manner, would attempt to despoil

form in the service of some 'alien content'. The customs

officers of formal integrity mount a constant battle to

retain the soiled virtue of form, in fact there are many

institutions dedicated to it's preservation!

Content, stripped of its passport to form, is in this scenario

understood, through a leap of absurdity, as existing in

some form of non state, a void without form.

Extreme as my description may be, in substance I think it

captures the debilitating conclusions obtained through the

retarded form/content debate and as a counter I would simply

like to raise the question: in the very instance of the

enunciation of content, is it not given form? Can we even

conceive or talk about content, if not through formal languages

produced within the confines of historically specific ideological

formations? If content has form, then form convention bound

and historically produced must be understood as content

by virtue of accrued social usage.

With the dislocation of the form/content axis, we are forced

into re evaluating the validity of what is usually called

'authorial intent'. For if content is now understood as

incorporating formal considerations, which actually determine

the meanings constructed for a work through the play of

its particular grammer, then we can no longer talk in terms

of pre established meanings being communicated by an author

in a direct manner to a viewer, rather we have to consider

this as a process not of communication but of signification.

One open to the notion of negotiability of meanings, an

active process of construction, rather than the act of passive

consumption.

A signifying practice, through the play of signs with social

currency, offers a range of possible meanings produced in

the engagement with specific bodies of knowledge possessed

by the viewers. It is through this interplay, and the degree

to which they appear to function as valid representations,

that the very notion of coherence is produced and meaning

is fixed. It is a process constantly in flux, gone are the

certainties of simply communicating a 'fact' to an audience,

meanings have to be constructed and fought for in a dynamic

process with no end. Those who seek certainty and reach

for the secure, the fixed, and the solid are fossilised

in the process; history is full of the accumulated debris

of such mute gestures, they make up the landscape on which

the battles of today are now being fought.

In this context Connections should be posed in a questioning

tone rather than the demand for certainty in unambiguous

form. Caution and stealth would be appropriate lines of

development, allied to a healthy cynicism about the possibility

of any hard and fast results or meanings being secured.

In addition, an understanding of what constitutes questions

and how they are articulated, in part determines the answers

obtained. A significant art practice would need to incorporate

these insights within the very operation of its practice,

acutely aware of its own construction and the procedures

by which it could secure new meanings within the various

communities of audience.

This is perhaps more urgent when applied to the undercurrent

of this exhibition, suggesting as it does, the possibilities

of points of relation between the cities of Liverpool and

Manchester. In one sense the project must be seen as a curatorial

reflex, animated by a range of concerns, but beyond those,

it does assume that there are significant features of compatability

or relation between the two cities; but what are they? What

is this imagined backdrop of reference, and further, speaking

in a fairly utilitarian manner, what would be the function

of drawing out these connections in 1986, apart from the

mundane aspect of galleries in the two cities having exhibitions

to show.

|

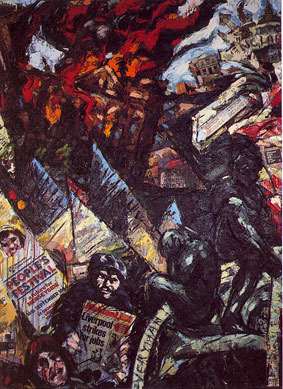

The

Red Town halls: Two Nations, Two Cities.

(Oil and

mixed media on canvas) |

Is it something particular about Liverpool and Manchester,

a special relation between the two?

In one sense this could apply, but the 'connection' will

be wide in its interpretation, or are Liverpool and Manchester

able to function in a much wider scenario, as representative

of other cities, situations, processes? Are they able to

be offered up as tokens as to what is happening on an extended

scale in 'the North' in Britain, Western Europe, in terms

of economics, politics and culture in 1986. In otherwords,

can Liverpool and Manchester be understood as condensations

for a range of complexities which are being restructured

at this time. It would seem to me to be the case that the

term restructuring can never be too far from our lips today,

as it is constantly inserted into a range of situations

often as a justification for actions with devastating social

results.

In any case when we speak of Liverpool and Manchester, what

exactly do we mean?

A geographic location, a political formation, the accrued

fabric of history in physical form, of buildings, of monuments,

of football teams, of specific cultural forms, of accents,

of manufacturing skills, of economic foundations, of history,

of futures or their possibilities? What constellation of

elements bind to make a Manchester or a Liverpool and are

they not in the plural? In what frame of reference are they

structured and is it that to which we must turn our attention,

of that which we must talk? It seems as if Manchester and

Liverpool and their connections are representative of elements

in operation within a much larger narrative; a narrative

whose process is given form in those complex entities to

which we give the names Liverpool and Manchester.

It would be the task of those partaking in this project

to sustain analysis of what grouping of processes are at

work and the representations they secure in very specific

forms. How Manchester and Liverpool are constructed as meanings

will help us produce an understanding of the rationale of

the system in which they are indexed and by which they are

determined. Liverpool and Manchester in 1986 will help us

understand the processes in which we are all implicated:

the struggle of the economic, political as well as the cultural.

What will be at stake will be the very notion of history,

its forces and mode of operation.

|

|

The

Burning of the Town Halls.

(Oil and mixed media on canvas) |

By

what process will all this be put into action? On entering

the exhibition space, what is to be our expectation of the

work and could not a sense of the unexpected be a legitimate

goal towards which we may work. What we must concede is

that we all have expectations about what might form the

substance of this exhibition. There are points of condensation

to which one would expect investigation to be directed,

we have notions of what Liverpool and Manchester and their

connections are. As to what these are; how they are produced

and reproduced and the degree to which they are seen as

'truthful' to our experience determines in part the kind

of meanings we can construct for the futureIt is a future

which seems to demand a quite radical break from the past.

For as they now operate in the present scheme of understanding,

to even talk about these cities as 'future' goes against

the current rationale, and to some extent this exhibition

would need to address itself to the situation in which Liverpool

and Manchester are being talked about as if they were synonymous

with history.

Not the living forces of historical processes, but a decaying

remnant an historical curiosity which, at worst, has to

be allowed or assisted to expire, so that it can be isolated

from the rest of the social body for fear of contamination,

or, at best, exposed to a form of selective preservation.

One in which the fabric of people's social existence becomes

a glorified 'theme park', where 'archaic' means of production,

stunted in physical form, become open air industrial museums;

mumification taking place at ever increasing speeds, history

veraciously consumed as just another set of objects to look

at on a Sunday afternoon. We are becoming a division of

the tourist industry; our environments and history a huge

show case; so what does that make us the tourists or the

exhibits? .

This is a form of'history' which is unhistorical, for it

estranges the 'landscape' of production from the condition

which produced it and which in turn it reproduced. It is

a history which we are encouraged to consume, but not learn

from. We look at the objects of history, but they tell us

nothing other than this is history in these objects, today

we have different objects so things must have changed! Look,

things were bad in the past; crude, noisy, dirty, oppressive,

but now that this is no longer the case, we have advanced.

History is ordered, it can be checked in catalogues, it

is safe and even quaint it certainly cannot harm us.

How then do we insert the 'historical' back into our environment

and the way we make sense of it; how can we learn from it,

so that we become the subjects of our history? How can we

produce an understanding of history not as a group of objects,

but as a dynamic process shaping our lives and our futures?

This

is a task that has to be put into operation and it demands

a fluidity of approach, one in which the construction of

the artwork not only articulates the diversity of signs

making up our experience of the world, but also that the

manner of their organisation constitutes a historical process,

which must be understood.

So what kind of practice will this involve?

One capable of carrying within the mechanics of it's own

operation the complexities of meaning. Not only does it

have to produce meaning, but it would need to lay bare the

process by which it did so, it must attempt to achieve a

dialectical unity in which 'meaning is process', a process

in which the viewer is actively engaged. This engagement,

in an attempt to produce knowledge, may be one fissured

with uncertainty, inquiry and even difficulty; but it does

not adopt these conditions for their own sake, as a form

of elitist foil, rather they are the conditions for moving

beyond the role of passive consumer and fulfilling a much

more demanding one, that of a participant in the production

of knowledge.

Collage, in its much wider definition, would seem to be

a process in which this attempt could be best achieved;

at least it extends in a diverse manner the opportunities

for the mechanics of representation to be exposed. Collage

represents a radical break in the techniques of composition

developed since the Renaissance, and is distinguished from

the tradition of the fixed view point and it's schema of

illusionism, by the insertion of fragments of reality into

the painting; material left unchanged by the artist. In

such a moment there is a destruction of the unity of the

painting as a whole, for the system of representation based

on the portrayal of reality fashioned by the subjectivity

of its creator has been breached.

When a glove or a piece of product packaging are glued on

to a canvas, they are no longer merely signs pointing to

reality, but they are fragments of reality. They act as

blockages to the apparently seemless flow of knowledge produced

within those systems of representation, disrupting their

naturalness, and in the same instance, in a reflex of self

exposure, drawing attention to the fact that it is a system

of representation, bound by convention and historically

produced.But what of the complexities which produce Manchester

and Liverpool? One aspect could be the 'historical' nineteenth

century Manchester and Liverpool; the municipal solemnity

of it's architecture, the grandiosity of a confident and

successful bourgeoisie in the form of public display of

power and stability; order posed in architecural as well

as social terms.

The remnants of that phase of industrial development still

litter the urban environment, now in the form of shadows

around which we physically experience the city, but shadows

also in the sense that the power which enabled their construction

and of which they were proof and celebration, has seemingly

moved elsewhere.In the move to display and fix an economic/political

power in architectural form, we witness the fossilisation

of that form as power; the limits of that power, its identity

as a historical 'present' in a process which never lingers

which always moves on and has to continually revolutionise

itself. Yet how can this be maintained when simultaneous

with the demand to revolutionise is the imperative to present

itself as order the natural culmination of a process of

modernisation. This is the millstone around the bourgeoisie's

neck; forced to deny the character of its own identity,

it adopts the mantle of disguise; a desperate game of bluff

and reassurance ensues. Nonetheless revolutionary the bourgeoisie

were; Marx writing the Communist Manifesto in 1848 could

write: 'The bourgeoisie, in its reign of barely a hundred

years, has created more massive and more colossal productive

power than all previous generations put together.

Subjection of nature's forces to man, machine,' application

of chemistry to agriculture and industry, steam navigation,

railways, electric telegraphs, clearing whole continents

for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations

conjured out of the ground what earlier century had even

an intimation that such productive powers slept in the womb

of social labour?" Marx goes on to point out that is

not only productive power that sleeps in the womb of social

labour, but that the bourgeoisie, through their relations

of production, brought about an enormous accumulation of

workers, who through their organisation and concerted action

achieve massive feats of production. This process also demonstrates

the power of organisation and concerted action as a means

to other ends; towards goals not directed at simply making

a profit, but which embrace the diversity of human potential

and need. The bourgeoisie have set in operation a model:

that of organisation and united action; they have shown

it to work, and this is the danger for in showing it have

they not provided the weapons for their own destruction?

Could not men and women organise and work together and fight

to change the world even further; must we simply accept

the structure of our society, the bourgeoisie didn't so

why should we?

It is with this realisation that the bourgeoisie attempts

to deny its own identity as being a product of a revolutionary

process; "if there was a process and it were once revolutionary,

then itisno longer, is the reply offered; it has reached

its culmination in the existing social order the bourgeoisie

are the end stop, or so they would like us to believe. Ushered

away is the history of continual overthrow of all previous

orders, for if this was not denied, then whatwill prevent

the conclusion being drawn that the bourgeoisie will likewise

be subjected to the same fate. Overthrown by the class formed

within the relations of bourgeois production: the proletariat

what exquisite irony!

So

we have the paradox of a system, animated by the need for

constant revolutionising of the means of production, denying

further revolution and attempting to make solid and monumental

that denial. In the end, of course, it is the process which

the bourgeoisie themselves put in operation which will prevail,

it is central to their very definition and infuses their

every action.