Project 8 'Letters to Language',

Solo Exhibition, Cornerhouse, Manchester 1996

'‘Letters

to Language: Dear Missing’

Foreword

Pete

Clarke is an artist who combines images of the urban landscape

with fragments of text which can or cannot be connected

to the painted image. There is a perversity of the delight

of using painted language juxtaposed with the freedom and

openness which Clarke employs on his canvas through the

use of texture and colour. Clarke alerts us (as does James

Joyce) that language is as gestural and transformative as

the physical stuff of oil paint on canvas.

Clarke's

dialogue with the spectator is not however played out in

a polemical way, his pragmaticism is displayed through the

physical properties of the surface which show a considered

process of intensive making over many months.

'Letters

to Language' has a materiality about it that brings art

back from the abyss of the super information highway. Clarke's

paintings transmit a personal and intensive flow of communication

but it is a dialogue that each spectator comes to in their

own time not by the press of a keyboard but through the

emotions of quiet reflective contemplation.

Stephen

Snoddy

Curator

In

Praise of Slow Communication

By

Sean Cubitt

Greenbank

Road Studio installation on 'Capital' 26 interrelated paintings

1992 -1996

The

business, the busyness, the industry, the financial glyphs,

the race of colour. fragmentation and oblique brushstrokes

that since the futurists have been the breathless iconography

of speed, the dromocratic hegemony of the 20th century's

modern: you want, in an impossible search for translation,

to list methods and motifs in hurtling, punctuated sentences

as fractured as these composite canvases. But to add prose

percussion to the fast surfaces of the Letters to Language

would be to promulgate a profound misunderstanding, that

comprehension can be undertaken at speeds greater than the

processes of making. James Joyce once asked his readers

to take as long to read the Wake as he did writing it. (Perhaps

half a dozen crazed academics have done just that. A certain

sense of proportion is necessary after all).

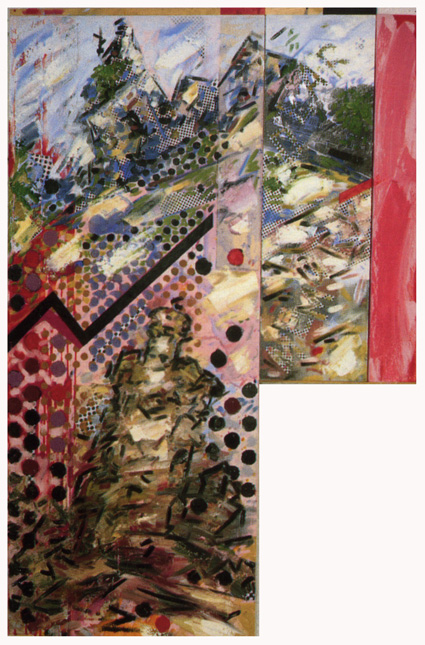

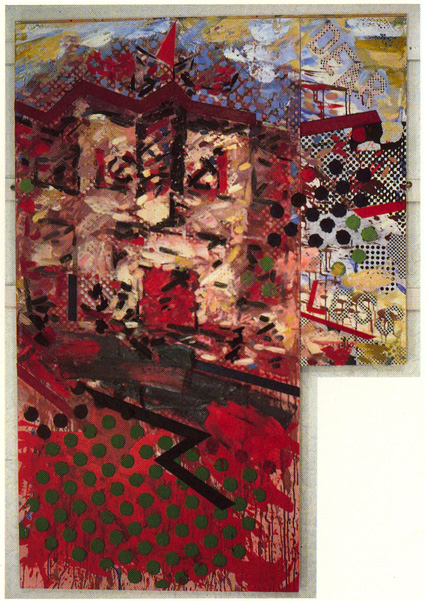

'Capital'

Series Hope I X I V I U / Guilt

Capital'

Series Hope

Joyce's

remaking of the medium of language, as a medium, and as

the medium of thought and fantasy, the intimate medium,

is one pole of a modernism whose other cryptic extreme is

the utterly external analytic of the medium undertaken in

Duchamp's Large Glass, one of whose titles is Delay in Glass.

That delay has something to do with the slowness of glass

plate photography, the minutes of stasis required of those

Victorians, posed in deep thought among unmoving sunlit

graves, that Walter Benjamin describes.

'Capital'

Series Belief

'Capital' Series Guilt

And the lazy relay of the fall of light on some distant

afternoon delayed a century or more until we come to look

at its effect. The delay, most of all, that might occur

as, passing through the galleries, you stop, intrigued,

to allow one work to work as you work, tracing the fractal

gravure of that old light.

Not New

: Not Changed 1994

‘Changed:

Not New’ 1999

In

Pete Clarke's canvases, such delays occur, between the intimacies

of Anna Livia Plurabelle and the cold edge of words, the

ontological refractions of the Large Glass and the psychomorphisms

of The Bride Stripped Bare. Iconography, technique, composition

and installation, the categories of canonical analysis and

post structural interests in the materiality of art, meld

upon the single ground of the choice of paint, which is

no longer a simple, neither categorical nor a cure. But

it is, as Clarke practices it, work of and in representation

which unpicks the obsessive speed of both technological

media and their commentators, a considered art of consideration,

a lethargic mulling through the Süt?,wein of picturing,

in which Lethe's considerate waters wash the viewer's, as

the painter's, responses of their habitual accretions, standing

pictorial evocations over against the immediacy of media

that seek invisibility.

|

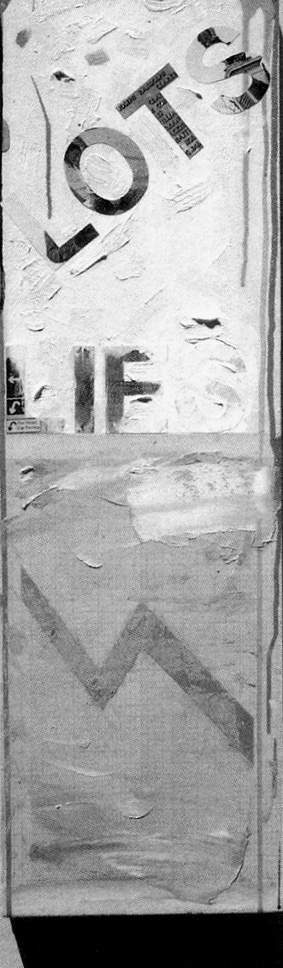

'Letters

to Language Installation : Code names 3 Month Gallery, Liverpool

1996

The

Letters, first, are letters, typographics, fonts, calligraphies,

themselves composed, discomposed and recomposed as print,

stencil, découpage, collage letters restored to the

chill air of denatured abstraction even as they fall from

the insensate grace of reason to private symbol and the

irredeemable personality of the hand. Like a child learning

that b is a fat boy hiding behind a wall, the letters which

painting sends back to language are at the same time the

minions of the information economy and the brute and unresolvable

forms of a dyslexic pictography whose every phase and phase

transition slows down transmission, until the medium challenges

the message.

'Letters

to Language' 'Dear Artifice' 1995 (detail)

Few

digital artists are as profoundly influenced in their work

by the materiality of informatics

as Clarke is in this obsolete praxis. Painting is important

today becauseit

is dead. To protest the death of painting is as futile as

protesting the death of God. But in its afterlife, painting

attains the critical delay which, in separating it from

the urgent quotidian, turns it into the ghostly ancestor

that haunts the hypermodern feast. Like Tiresias, this shade

that has been everything and now is nothing brings the sharpened

edge of prophecy to visual politics.

Today, in the era of vision's triumph, the politics of vision

has fallen victim to its own haste.

|

'‘Letters

to Language: Dear Memory’

No longer a matter of representation, Western visual culture

has become the terrain of symbolisation, of graphemes isolated

from their discourses, pictures separated from what they depict

by the very speed of their circulation. The relation between

world, medium and audience has been cauterised in the substitution

of information for world, and transmission for mediation,

to create the isolation of the modern consumer. The works

in both Capital and Letters to Language become the slow harbingers

of a vacuum at the heart of semantic functionality. They are

not works about the collapse of meaning, but about the vacuity

of this vacuum: the difficulty of meaning under a triumphal

capitalism that seeks to erase it under the fetishised commodity

form, as utility and as exchange. The work of Clarke's canvases

is to rediscover meaning as that relationship between people

which, as Marx has it, appears to them as a relation between

things.

|

'Letters

to Language' 'Dear Abstraction' 1996

The

uncritical accolades for intertextuality that litter art

and cultural criticism over the last 30 years misunderstand

the processes of capital: the intertextuality of the Sunday

colour supplements is precisely a relationship between media,

as objects: not people, not subjects. Like the Dionysian

terror that haunts the Apollonian iconography of Poussin's

Landscape with the Ashes of Phocion, migrated from Liverpool's

Walker Gallery to the composition of Dear Memory, the violence

done in the name of King Cash underwrites the classical

architectures of banks, the geometric purity of fiscal graphs.

But where Victorian modernity clung to the icons of stability,

the accelerated demands of globalised info capital celebrate

the stasis of the whirlwind, the mocking zen of the strange

attractor. Capital need no longer fear Marx's piercing analysis

of 'all that is solid melts into the air': it has made change

and velocity its own heraldic devices. Everyone sees the

whizzing images: no one notes the still frame of the TV

screen.

|

''Letters

to Language' Greenbank Road Studio Installation 1996

These

paintings do not abandon meaning, value or reason. With

the use of serial techniques like screen printing and èolour

photos, Clarke addresses the fall of passion into its signifiers

as analytically as his bravura paint handling, not the expression

of inner turmoil, but an investigation of what it means

to make that passionate engagement conform to a lexicon

of formalised techniques. We know that the expressionist

move in modern painting has always come up against the formalisation

of its classic gestures, just as Hollywood's stars give

us the common vocabulary of lust and anger from a database

of grimaces and tics as familiar as the alphabet. We know

too that the fragmentation of vision among the impressionists

became the foundation of mechanical vision, from colour

photography to satellite surveillance. The 20th century

history of graphic design is a prolonged attempt to recover

from the isolation of letters on the typewriter keyboard;

of cinema to anchor the autonomy of the human in the autonomy

of the machine; of science to rationalise the inhuman. Our

epoch is one swaying drunkenly between reason and madness,

two halves torn apart in the administrative logic of an

economy that still requires the fury of invention for its

survival.

|

'Letters

to Language' 'Dear Loss' 1996

If,

as John Roberts argues, painting is peculiarly suited to

carrying out work on history, Clarke is a painter. The point

of the work is not to urge a reconciliation between rationality

and passion the undertaking of Matisse, uniquely the most

typical of modern painters but to understand the histories

of their divorce. Take the motif of the folly in these works.

Architecture is supposedly the art of space, abstracting

from the sheer dimensionality of the world forms for habitation.

Yet most architecture, quite apart from its apparent ignorance

of time, administers the rigourously managed spaces of Cartesian

geometry. Only the folly, purposeless it seems, serves not

only as the antiphonal descant to architecture's reason,

but as the persistence of another mode of thought, the critical

modernity of Erasmus' Praise of Folly, whose satire modulates

into celebration of Christ's folly in dying on the Cross:

the folly of redemption. The monument builder, as engineer

of madness, is the type of the artist, caught in the stupidity

of trying to construct a critique of commodity communication

within a commodity form, like the supernatural in a mortal

body.

Clarke's

pragmatism is as much a matter of the making of the work

as it is of its ostensible content. The canvases are worked

as surfaces and as labour and urge a recognition of that

work which mass culture denigrates in its entertainments

and its assumption of the pose of effortlessness. So, for

example, the 'expressive' brushwork not only functions as

critique of expression, but returns as a meditation on the

artisanal, the traces of a making which continues over months

and is abandoned rather than completed. The alphabet of

Capital is such a project of incompletion, not as resistance

to or subversion of the dominant mode of communication,

but as an alternative circulation, its difference derived

from the internal differences of language as alphabet and

as speech, but pledged to a conception of communication,

even of communion, which is excluded from the commodity

form.

The

Letters to Language face a different problem, metaphorically

the problem of the missing address: where should these letters

be sent? The paintings' legends give us Clarke's pro tem

solution: Dear Memory, Dear Loss, Dear Deficit, Dear Artifice,

Dear Monochrome, Dear Missing, Dear Shadow, Dear Abstraction...

In the delay between painting and language, and from the

perspective of painting, language, as information and transmission,

is a process which historically has removed itself from

a materiality to which painting might lure it back. Abstraction

is not a point of origin, but a labour in which you remove

the trappings of the actual in favour of the stable shape

of the ideal. But that ideal increasingly resembles the

commodity itself, gradually stripped of use to approximate

the final signified of contemporary capital, total consumption,

without object or subject. The testimony of this impossible

abstraction, the lure of the reconciliation of individual

and world in their mutual annihilation, gives Clarke his

addresses. The serial form itself mimics the industrialisation

of communication only to unpick its internal dialectic of

emptiness and plenitude.

|

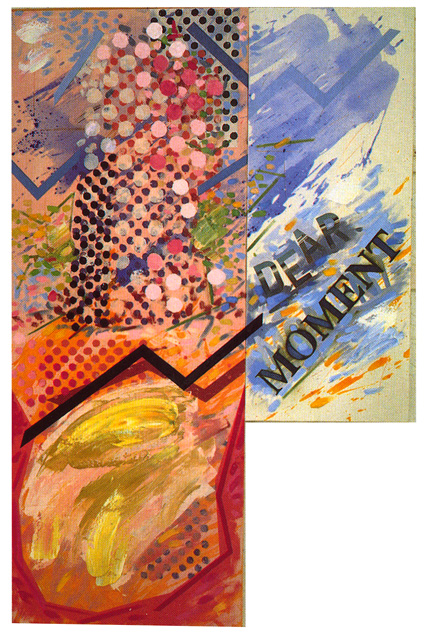

'Letters

to Language' 'Dear Moment' 1996

The

force of the works here is not to expose or even to reject

these dialectical prisons of the communicative universe.

In our historical condition, that is no more important than

telling us that there is light in the room. Communication

is unavoidable: to communicate and to be human are synonymous,

though communication has been transformed, over centuries,

into economy to the point that all communication has become

economic in some way. The effort has to be first to maintain

the possibility of communication through the struggle to

communicate. Here, all is delay, even more than it is lack

or loss. The letters all arrive aftei language has already

moved on, discovering in its place its traces deficit, memor\

shadow. These are the conditions of the contemporary obsession

with an impossibft instantaneity, the dream of the utterly

transparent, utterly efficient messag couched in the language

of speed. The material of communication is its inconvu nience,

in the sense that its real duration and distance demands

calm moments o otiose exploration, a return to pleasure

in the place of excitement.

|

And then, to explore the grounds on which communication

may occur at all. In the choice of painting, Clarke chooses

silence, but in his use of letters, instigates another,

inner speech, an activity of interpretation in the very

place, at the heart of transmission, where information engineering

insists that there is neither medium nor content but pure

flow.

To instigate interpretation, with all its commonness, sociality,

misunderstanding and argument, its democracy, at the site

of the Black Box as Clarke has done is to gum up the works,

not as sabotage, but to discover whether, as the viewer

opens the box, and the monsters at their breathtaking velocities

fly out to plague us, there may be some Pandora's jewel

resting at the bottom, the slow gemstone of hope.

Sean

Cubitt is a Reader in the Department of Media and Cultural

Studies at the

Liverpool John Moores University

Acknowledgements

Thanks

to the Department of Art and Fashion, University of Central

Lancashire, Preston for support in publishing this catalogue

Thanks

to Sean Cubitt for his catalogue essay and critical practice

Thanks

to Stephen Snoddy and Cornerhouse for their help and support

Thanks

more than ever to Angie, Joe and Tom

Pete

Clarke September 1996